PERSONA GRATA

Niels Blokker:

Law of international organizations in the 21st century: features of research and teaching Interview with Niels Blokker, professor at the Hugo Grotius Center for International legal studies at Leiden University (Netherlands)

Interview with Niels Blokker, professor at the Hugo Grotius Center for International legal studies at Leiden University (Netherlands)

№ 9 (148) 2020

Biography

Biography

Niels Blokker is professor of the law of international organizations at the Grotius Centre for International Legal Studies, Leiden University, the Netherlands. He graduated from Leiden University (1984), where he also defended his dissertation (1989). From 1984 he was a lecturer, subsequently a senior lecturer in the law of international organizations at Leiden University. In 2003 he was appointed as part-time Professor of International Institutional Law to the Schermers Chair. Since August 2013 he is holding this Chair on a fulltime basis.

In 2000 Niels Blokker was appointed senior legal counsel at the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs. From 2007 until August 2013 he was deputy legal adviser at this Ministry. Niels Blokker has published books and articles on a variety of international law issues, in particular related to the law of international organizations. With the late Henry G. Schermers, he is the co-author of International Institutional Law (6th edition November 2018). He is also co-founder and co-editor in chief of the «International Organizations Law Review».

LAW OF INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS

– You are the co-author of a world-famous textbook on international organizations. The latest 6th edition in 2018 has over 1,300 pages. You presented this book to our department and now students and graduate students have the opportunity to use this book. Thanks a lot! How do you think international organizations have changed? How has course teaching changed over the decades?

– I am afraid that my short answer in the context of this interview cannot fully do justice to the scope and depth of these questions … Anyway, let’s try. In my view, the essence is the following. Because of technological revolutions and globalization states loose some ‘governance control’. It is in their own interest to cooperate internationally, partly through international organizations. In addition, a number of key problems are by definition international and cannot be solved at the national level only (e.g. climate change, terrorism). As a result, during the last few decades, the role and activities of international organizations have increased. But this has also triggered resistance, see the current waves of nationalism and populism. Nowadays, international organizations are sometimes scapegoats for things that go wrong at the national level, or for anything from abroad that is disliked. To some extent they are the victims of their own success … We see this at the global level, but also regionally (e.g. Brexit).

These grand long term developments obviously affect the law of international organizations. For example, the development of the ILC articles on responsibility of international organizations (ARIO) may partly be explained against this background. In 1963, ILC rapporteur Ago could still write that it was “questionable whether such organizations had the capacity to commit internationally wrongful acts”. Such a view is now completely outdated, and under the leadership of Ago’s compatriot Gaja the ILC prepared the ARIO. Nowadays, the broader topic ‘accountability of international organizations’ is a popular topic for conferences, blogs, student papers, etc. However, an old lesson is that we always need to distinguish between the organization and its members. We should not forget about accountability of the members. If we want to know why the WTO Appellate Body no longer is in operation, or why the ICC does not deal with the most serious crimes of international concern in Syria, we first of all need to look at states.

All this has obviously also influenced teaching. First of all the topics included in courses on the law of international organizations – they should now include responsibility issues. However, the biggest change in my teaching in this field is one of the manifestations of globalization: student exchanges and the internationalization of my classroom. When I started teaching in the 1980s, all my students were Dutch. Now, most of my students are international students and come from some 30 to 40 different countries in all parts of the world (including students from Russia!). A number of international Moot Courts exist in which these students can participate and learn international law ‘in practice’. Since the 1970s Leiden University organizes the ‘Telders International Law Moot Court Competition’, in which usually some 20-25 European Universities participate, with Finals in the Peace Palace in The Hague. This year the RUDN University also participated. Unfortunately the oral pleadings had to be cancelled because of the corona travel restrictions.

The ‘internationalization’ of the classroom has greatly enriched my job as a teacher, and hopefully also the experience of students. This is the way to assist the future generation to deal with challenges such as the ones mentioned above.

– The trend of our time is the withdrawal of states from international organizations and bodies. Thus, the United States withdrew from WHO, UNESCO, the UN Human Rights Council; Great Britain leaves the EU; Burundi and the Philippines withdrew from the International Criminal Court; Japan withdrew from the International Whaling Commission. How do you assess this trend?

– Indeed, this seems a trend today, reflecting the nationalism and populism that is strong in some countries. However, as always, research helps to put things into perspective. ‘Facts kick’, as the Swedish sociologist Gunnar Myrdal once wrote. Alternative facts (‘fake news’) don’t. There have always been withdrawals from international organizations. The Soviet Union and other Eastern European countries withdrew from the WHO and from UNESCO, the US from the ILO in 1977, and there are many other early examples. So this is not something really new. And what is interesting: in most cases (including the mentioned withdrawals from WHO, UNESCO and the ILO) the states that left rejoined later. You can withdraw from an international organization, but you cannot withdraw from globalization. My colleague Ramses Wessel referred a few years ago in the context of Brexit to a line in a song by the Eagles (Hotel California): ‘you can check out any time you like, but you can never leave’. In the long run, it is in the self-interest of states to be involved in the governance of globalization.

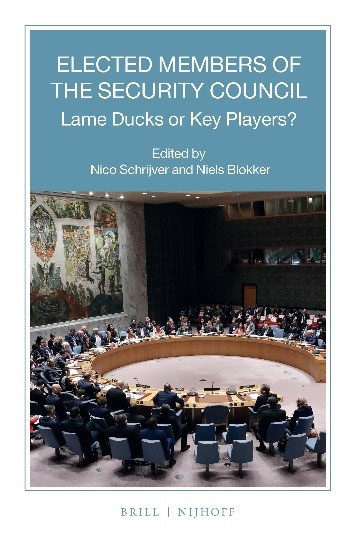

– This year a monograph was published on the activities of non-permanent members of the UN Security Council. You are the co-author and co-editor of this book. It should be noted a very extraordinary approach to the study of the UN Security Council. What are the main conclusions you would point out in this regard? Are they «Lame Ducks» or «Key Players»?

– In between! While it is not true that non-permanent members are key players, it is equally untrue that they are lame ducks. In our book, it is convincingly demonstrated by several contributors, both academics and practitioners, that non-permanent members have been active and successful in the Security Council, in particular areas such as the promotion of the rule of law, sanction reform and criminal justice. Those readers who want to know more: read the book!

– In addition to being a professor, you have worked for many years at the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Thus, you are the owner of theoretical and practical knowledge. Moreover, in 2019 you took part in an academic conversation «Two souls in one breast: the international institutional lawyer as scholar and as practitioner». Do these “souls” often conflict?

– Indeed, for many years, until mid-2013, I had two jobs: one day each week I worked as a professor at Leiden University, the rest of the week at the Dutch MFA. I feel privileged that this is possible in the Netherlands. In many other countries this is not possible, for different reasons. Having been in practice has surely influenced my academic work, both teaching and research. In my research I am fascinated by the relationship between law and practice. In Winter 2022 I will teach for the Hague Academy of International Law, and my course will be devoted to this topic, in the context of international organizations.

It was almost never difficult to have ‘two souls’ in my breast. Perhaps the only exception relates to the invasion in Iraq in 2003. In the MFA I had prepared confidential legal opinions on the (il)legality of this invasion. At the time, I did not feel ‘free’ to write an academic article about the same issue. Perhaps it helps that the law of international organizations is often not dealing with such delicate, sensitive political issues as the Iraq invasion. It also helped that my government fully allowed me to have my own views – of course in my capacity as a professor – that would not necessarily be the same as those of the government. If it would be otherwise, I could not have done my work as an academic properly and honestly, in particular at Leiden University whose motto is ‘praesidium libertatis’ (bastion of liberty)

– In addition to international organizations, you have a lot of works devoted to international courts. Before moving on to this topic in the interview, I would like to note that you have found a joint problem for these two branches of international law. Recently, you have raised very interesting questions that previously dropped out of the subject of close study. I mean the institutions for the management of international courts, or as you call them “INJUGOVINS” (international judicial governance institutions). Tell us more about them. In your article, you noted that it was the Meeting of the Parties of the States Parties to the UNCLOS that, in comparison with other similar mechanisms, achieved good results in interaction with the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea. How is it shown? What prevents other mechanisms from building such relationships with international courts?

– As to ‘injugovins’: the topic is under-researched. There has been a fast and impressive growth in the number of international courts and tribunals over the last three decades. From 6 in 1990 to some 30 now (even more than 50 if we also include international administrative tribunals). Their role and functioning affect international law and international relations, as has been analyzed in many books, articles, and in recent years also in blogs, podcasts etc. International law and international relations have increasingly become ‘judicialized’. The research focus has very much been on the courts and tribunals themselves, analyzing their functioning, their judgments. This is excellent and necessary, and it should continue. However, within the field of international law, hardly any attention has been given to the governance of international courts and tribunals. This is why I started doing research into the governance of international courts and tribunals during the last few years. It is urgent. Many international courts and tribunals are facing difficult questions and strong criticism relating to their governance, ‘the way in which they are run’. See the ICC and the WTO Appellate Body in this context. The Tribunal of the Southern African Development Community was even effectively closed by the 15 states involved after it delivered a judgment that the Mugabe government of Zimbabwe did not like. If we care about international law, we care about how it is applied by international courts and tribunals, and therefore we should care about their functioning. We need to take the governance criticism seriously and address it. Well-performing international courts and tribunals are good for international law and for the international legal order.

As to the Meeting of the Parties of the States Parties to the UNCLOS: I have no final conclusions why this injugovin has been more successful than others. But certain elements may play a role. The budget of ITLOS is relatively small, some of the more political or politicized law of the sea issues are not discussed in the framework of this Meeting of the State Parties (usually in June), but in the context of the UN General Assembly in Fall. In addition, ITLOS had an excellent registrar for many years after its establishment: Philippe Gautier, who is now the Registrar of the International Court of Justice.

INTERNATIONAL COURTS

– Not so long ago, you co-organized a very interesting conference on international courts and tribunals. The two-day conference was attended by judges and employees of the International Court of Justice, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, the WTO Appellate Instance, the International Criminal Court, the EU Court, the EAC Court and other experts. Tell us what trends prevail today in the field of international justice?

– This was a wonderful conference (Sept. 2019) , in which we wanted to launch this research project. I have organized it with three colleagues, including dr. Sergey Vasiliev (who is now with Amsterdam University). We had very substantial keynote speeches by President Yusuf of the ICJ and President O-Gon Kwon of the ICC Assembly of States Parties. Sergey is now taking the lead in preparing a large edited volume on the basis of this conference, to be published probably in 2022.

– What do you think about the thesis “The International Criminal Court” is created exclusively for Africa “?

– This thesis is completely wrong. This Court was established to deal with the most serious crimes of international concern, wherever in the world they are committed. The Court follows the principle of complementarity: if the relevant states are ‘able and willing’ to investigate and prosecute the crimes concerned, the ICC does not need to be involved. So: if African states take this principle seriously, the ICC does not need to ‘step in’. In addition, in a number of cases, African states themselves have referred situations to the ICC. Finally, the ICC Prosecutor is also carrying out investigations concerning situations outside Africa.

– Once you invited a participant of the Nuremberg Tribunal from the USA to a lecture at Leiden University. Tell us how it went.

– This was Benjamin Ferencz, who has turned 100 in March of this year. I met him often in the context of the crime of aggression negotiations, and invited him to come to Leiden and give a guest lecture. The students will never forget this experience. I did his PhD in Harvard during the Second World War, participated in that War as a soldier, including in the liberation of concentration camps. At Nuremberg, he was the Prosecutor in a major case, dealing with the Einsatzgruppen, responsible for the killing of about a million people in Central and Eastern Europe. After that he has always worked hard for the establishment of an International Criminal Court. For many years, during the Cold War, this was politically impossible. But his motto has always been: ‘never give up’. This is certainly one of the many things we can learn from him. There is a short video about his guest lecture at Leiden University on YouTube, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QIi4-L9DaTs&feature=youtu.be

LEIDEN UNIVERSITY

– Leiden University has existed for 445 years. It’s colossal! Hugo Grotius himself, Tobias Asser, Ben Telders studied at Leiden University. In the immediate vicinity of the International Court of Justice, the International Criminal Court. How does it feel to work at Leiden University?

– I feel privileged! This is my alma mater, where I was also lucky to find my promotor Henry Schermers, an inspiring mentor to whom I have always felt great loyalty. Indeed, at Leiden we are very close to The Hague. It takes much less time to travel from Leiden to the Peace Palace (the home of the International Court of Justice) or to the ICC, than to travel from Moscow Airport to the city centre. Judges of both international courts regularly come to Leiden for guest lectures or conferences. Leiden University now also has a Faculty in The Hague that has grown impressively during the last two decades.

– You graduated from this University and work here. Is this typical for Holland? You work at Schermers Chair. Could you please tell us more what does it mean?

– I don’t think it is typical in the Netherlands to both study and subsequently work at the same university. It is true for me and some of my Dutch colleagues. But others have become professors at other universities than their alma mater.

The Schermers Chair has a special history. When Schermers gave his farewell lecture in 2002, he announced that he would donate to the university most of the money from selling his beautiful old canal house. This is of course an exceptional gift. He was following the example of a few predecessors at Leiden. This donation enable the university to establish the Schermers Chair, on which I was appointed in 2003. I feel privileged to be on this Chair and feel very committed to it.

– Leiden University was known for its anti-fascist stance, also due to the position of Professor Rudolph Cleveringa. Please tell us about it.

I am glad you ask this question. Again it is difficult to give a short answer. You can find more information and a short film here: https://www.universiteitleiden.nl/en/dossiers/the-university-and-the-war/cleveringas-biography

Most of what now follows is taken from this website.

In May 1940 the Nazis attacked the Netherlands. Gradually they enacted anti Jew and other Nazi laws. At the time, Rudolph Pabus Cleveringa (1894-1980) was the Dean of the Law Faculty. On 26 November he delivered his now famous protest speech, in which he denounced the measure taken by the invading Germans of removing all Jewish professors from their posts. One of these professors was Cleveringa’s colleague Eduard Meijers, who should have been lecturing his students at that point in time.

Cleveringa was arrested by the Security Services and remained in prison in Scheveningen (familiarly referred to as the ‘Orange Hotel’) until the summer of 1941. Having listened to his speech, the Leiden students decided to go on strike, a step that Cleveringa had by no means encouraged them to take. The University was then closed down by the occupying forces.

In 1944 Cleveringa was imprisoned in Vught. He became a member of the ‘College of Trusted Men’ that coordinated the resistance. After the war had come to an end, he resumed his work at Leiden University until 1958, when he retired. He was made a member of the Council of State and continued in this role until 1963 when he became Councillor of State Extraordinary. He died at the age of 86, in Oegstgeest near Leiden.

– How is Leiden University living in the covid-19 era?

– We had to interrupt regular teaching in March 2020, including my own master course on the Law and Practice of International Organizations. Fortunately, within a week we were able to re-arrange most of our courses online. Since September, in the new academic year, we have decided, just like other Dutch universities, to give physical classes on a priority basis to first year students and to master students, respecting the COVID-19 restrictions. Other students follow all or most of their courses online. All of us, teachers and students, realize now even more the added value of physical classes. Whenever possible, we will do this. But the coronavirus loves students (and other young people)! Students are now a major source of infection, so we need to be very careful.

In my experience, COVID-19 is not good for teaching but may create an opportunity for research and writing. In my quasi quarantine at home, I was able to prepare a book on the UN Security Council, to be published in November this year (‘Saving future generations from the scourge of war’).

About science

• Dear Niels, you are a very fruitful scientist! Can I ask a little about your “scientific kitchen”? How many articles do you write at the same time? How do you decide which articles to write in Dutch, and which ones in English? Is there a need for classical libraries today or do you have enough online journals and research materials? What journals would you recommend for reading? In which conferences do you participate annually?

– As a cook in this kitchen, I have no secrets for your readers. Most of what I publish is in English, but there are also materials in Dutch. The advantage of writing in Dutch is that this is my native language. Since law is also about language, I feel that I can express myself sometimes better, with more nuance. However, outside the Netherlands not many people read Dutch. And also because I work in a rather specialized area, it is often better to use English so that I can be in touch with my colleagues abroad who refuse to learn Dutch.

I do not regularly attend the same conferences, it depends on what is discussed. The European Society of International Law is a very useful Forum, also for younger academics. I have no favorite int. law journal. I am very proud to have established with prof. Ramses Wessel the journal International Organizations Law Reviews, established some 16 years ago. We are still the two Editors-in Chief, and we have a dream team as editorial board. The journal is doing very well, and there are now three issues published each year.

• Dear Niels, which book on international law could you recommend for reading? For example, the book you are currently reading or that made the biggest impression on you.

– Karen Alter, The New Terrain of International Law (on the increasing number of international courts and tribunals and their impact on international law/ international relations). Also, for its clarity on a topic all states embrace: Tom Bingham, The Rule of Law. And, in order to never forget: Primo Levi, Survival in Auschwitz (bad translation of the original Italian title Se questo é un uomo). I am now reading Philip Glass «Words without Music».

• On April 2019 you took part in the international congress “Blischenko Congress” at the Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), and then delivered a series of lectures on international institutional law and international courts and tribunals. We were also expecting you this year, but due to COVID-19, unfortunately the trip had to be canceled. How do you like Russia, Russian science, RUDN students?

– It was a wonderful experience last year to come to RUDN University, to see its international orientation, and to contribute to the Blischenko Congress. I thoroughly enjoyed the discussions I had as well as the hospitality offered. Hopefully we will soon overcome COVID-19 so that international conferences such as the Blischenko Congress can be organized again. I look forward to come again.

CONCLUSION

• Taking into account, how much time you spend on science, do you still have time for a family, do you have a hobby?

– Of course, the only ones who can give a credible answer to this question are my wife and two children … I have always considered it essential in my life to maintain a proper balance between work and private life. In academia, it is easy to become a workaholic. There is an endless list of things to research. But I always wanted to avoid becoming a true workaholic. Besides, I also fully enjoy my private life! My main hobby now is classical music. I have played the piano since I was 6. Russian composers are among my favorite composers, Rachmaninov, Prokoview, Shostakovich. And on Sept. 13, we listened to a wonderful performance of songs written by the not-so-well-known Russian composer Nikolaj Medtner. He has written 108 songs. Perhaps he was not as innovative as composers like Shostakovich, but it is wonderful, sensitive, high-quality music, including songs based on moving poems by Pushkin.

• And finally, what would you like to wish the readers of our journal; we are followed today in all countries of the former USSR.

– I wish you success in your international law work and the best possible balance with your private life. Hopefully we can contribute to the improvement and stability of relations between our countries and peoples. Personal contacts across borders help to remove or reduce barriers and prejudices, build bridges, and opens new horizons. We are fortunate to have a common language that is international law!

Thank you Alexander for this interview.

Interviewer:

2,515 ВСЕГО, 2 СЕГОДНЯ